An Overview of RL Environments

Background

Reinforcement learning works on the FAFO principle → Fool Around and Find Out (more on this here). But to fool around, LLMs need a playground: an environment where they can take actions, observe outcomes, and learn from their mistakes.

In the above game, the player’s actions (↑/↓/←/→) decide the outcome of the game:

- Did you crash?

- Did you successfully cross the finish line? or

- Are you still racing?

This action → outcome loop is exactly what RL environments provide for LLM training.

The Anatomy of an Environment

Whether you’re training a robot to walk or an LLM to write code, the core interface remains the same (mostly):

class Environment:

def reset(self) -> Observation:

"""Reset the environment to initial state"""

pass

def step(self, action: Action) -> Tuple[Observation, Reward, Done, Info]:

"""Take an action and return the outcome"""

pass

In our car racing analogy versus LLM training, the parallel is as follows:

┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ RL ENVIRONMENT │

├────────────────────────────┬───────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ CAR RACING │ LLM TRAINING │

├────────────────────────────┼───────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Action: ↑ ↓ ← → │ Action: Generated text/code/toolcalls │

│ Observation: Track state │ Observation: Tool outputs, errors, feedback │

│ Reward: +1 forward │ Reward: Verifier score │

│ Done: Finish/Crash │ Done: Task complete / max turns │

│ Info: Lap time │ Info: Execution trace │

└────────────────────────────┴───────────────────────────────────────────────┘

The critical difference lies in the Reward. In a game, the score is built into the engine—cross the finish line, get a point. In LLM training, we need to define what correctness means and build logic to verify it. This brings us to the first concept: Verification.

Reward Verification strategies

Every environment needs to answer two questions:

- “Did the model do it right?”

- “Should we keep going?”.

In other words, we need a verifier to compute the reward and a criterion to decide if the task is done.

The verification method effectively defines what “good behavior” means for RL: the policy will learn to optimize whatever the verifier can reliably score. For math, this is often straightforward: extract the final number and compare it against a ground-truth answer. But for code, “correctness” is a spectrum rather than a single target. It involves satisfying a set of constraints—the code must run, produce the right outputs, and often meet style, safety, or efficiency standards. Naively string-matching source code doesn’t work because there are infinitely many equivalent implementations of the same function.

Code verification strategies have converged to five main approaches, each with distinct tradeoffs that affect training dynamics.

1. Execution-Only Verification

The most lenient check: just ensure the code runs without crashing. This is useful for open-ended creative tasks or assigning partial credit for syntactically correct code.

def verify_runs(code: str) -> float:

result = sandbox.run(code, timeout=5)

return 1.0 if result.exit_code == 0 else 0.0

For instance, CodeRL (Le et al., 2022) treated code generation as an RL problem with execution-based rewards, using a critic network trained to predict functional correctness from four outcome categories: compile error, runtime error, failed tests, and passed tests.

\[r(W_s) = \begin{cases} -1.0 & \text{if } W_s \text{ cannot be compiled (compile error)} \\[0.5em] -0.6 & \text{if } W_s \text{ cannot be executed (runtime error)} \\[0.5em] -0.3 & \text{if } W_s \text{ failed any unit test} \\[0.5em] +1.0 & \text{if } W_s \text{ passed all unit tests} \end{cases}\]We can see that instead of a sparse binary reward, we can get -1.0 (worst case: not compiled) or -0.6 (compiled but not executed), -0.3 (executed but failed any unit test), +1.0 (passed all unit tests) based on the outcome. This is a more informative reward signal that can help the model learn from its mistakes.

2. Input/Output Matching

Here, we run the code and compare output against expected results. This can be done via stdin/stdout (language-agnostic) or by calling the function directly with arguments. Seen in benchmarks like LiveCodeBench, APPS, and CodeContests.

def verify_stdin_stdout(code: str, test_case: TestCase) -> bool:

result = sandbox.run(code, stdin=test_case.input)

return result.stdout.strip() == test_case.expected_output.strip()

def verify_functional(code: str, test_case: TestCase) -> bool:

actual = sandbox.call_function(code, test_case.func_name, test_case.input)

return actual == test_case.expected_output

3. Assertion-Based Testing

Here, we wrap the solution in a test harness with assert statements (or unit tests). If the test script exits with code 0, the solution is correct. Seen in benchmarks like HumanEval, MBPP, etc.

Note: EvalPlus extended these datasets by generating 80x more test cases for HumanEval and 35x more for MBPP using automated input generation seeded by commercial LLMs.

def verify_with_assertions(solution_code: str, test_code: str) -> bool:

# assert candidate(input) == expected_output

# test_code contains: assert candidate([1,2,3]) == 6

full_code = f"{solution_code}\n\n{test_code}"

result = sandbox.run(full_code)

return result.exit_code == 0

The Reward Engineering Challenge

The reward function determines training dynamics more than any other design choice. The field has learned hard lessons about reward hacking, with frontier models now actively manipulating evaluation code when given the opportunity. For instance, SakanaAI had to walk back claims about their AI speeding up model training after discovering it was gaming the metrics. Similarly, METR’s O3 evaluation documented numerous reward hacking examples from OpenAI’s o3 model.

The Strict Reward Trap

Binary rewards worked surprisingly well for Deepseek-R1, but in practice, strict binary rewards on complex tasks can often stall learning as there is no success signal to guide the learning. One mitigation would be to further finetune the LLM (SFT) on the task solutions before RL training. But beyond that, we usually need to shape the reward better.

Partial Rewards: A Double-Edged Sword

Giving partial rewards for progress seems like a good idea. In coding, perhaps give 0.1 reward for passing a single test case out of 10 (so 0.7 if it passes 7/10 tests). This dense feedback can help the model improve incrementally so that it’s not all-or-nothing.

# Seems reasonable...

reward = 0.1 * moved_forward + 0.5 * avoided_obstacle + 1.0 * finished

However, dense rewards come with a trap: reward hacking. The agent might find a way to exploit the reward structure rather than solving the actual task. This is particularly problematic in environments where looping or repetitive behavior can accumulate rewards.

Reward Hacking

A classic example comes from OpenAI’s research on faulty reward functions. In the boat racing game CoastRunners,

The targets were laid out in such a way that the RL agent could gain a high score without having to finish the course. Instead of racing, it found an isolated lagoon where it could turn in a large circle and repeatedly knock over three targets, timing its movement to always hit them just as they respawned. Despite repeatedly catching fire, crashing into other boats, and going the wrong way on the track, the agent achieved a score 20% higher than human players by completely ignoring the intended objective.

Gaming the benchmarks

Reward Hacking has become alarmingly sophisticated. METR research (June 2025) found o3 reward-hacking in 100% of runs on certain tasks, with 30.4% hacking rate across RE-Bench overall. Documented exploits include: monkey-patching torch.cuda.synchronize to fake faster runtimes, tracing the Python call stack to steal the grader’s ground_truth tensor, patching evaluation functions to return “succeeded: True”, and overwriting PyTorch’s __eq__ operator to always return True.

So how do we avoid stalled learning from sparse rewards without inviting reward hacking? One effective strategy is to control the difficulty of tasks the model sees during training.

Curriculum Training

RL training is most effective when tasks are neither too easy nor too hard. Curriculum training solves this problem by dividing training into a few manually-defined phases of increasing difficulty (Wen et al., 2025; Luo et al., 2025; Song et al., 2025), but these are coarse-grained and lack adaptivity. Adaptive curriculum learning addresses these issues by matching problem difficulty to the model’s evolving capabilities.

RLVE (Zeng et al., 2025) introduced a large-scale suite of 400 math and reasoning environments that procedurally generate tasks based on the model’s capabilities as training progresses.

AdaRFT (Shi et al., 2025) maintain a target difficulty level $T$ that evolves based on recent rewards. When average reward exceeds target ($\beta=0.5$) (also proposed by DOTS (Yifan et al., 2025)), difficulty increases; otherwise, it decreases. Their approach uses an external LLM (Qwen 2.5 MATH 7B) to estimate difficulty based on the success rate over 128 attempts. They observed a 2x reduction in training steps while improving accuracy.

AdaCuRL (Li et al., 2025) addresses gradient starvation by partitioning training data into difficulty buckets and progressively merging harder buckets based on the accuracy reward of the policy’s current state. Crucially, earlier buckets remain in the training set after merges, providing a data revisitation mechanism to mitigate catastrophic forgetting. INTELLECT-3 (Prime Intellect Team, 2025) takes a lighter-weight approach: problems are sorted into difficulty pools (easy, normal, hard) based on observed solve rates, and sampling ratios from each pool are adjusted dynamically. An online filter discards trivial rollouts that provide no learning signal. Unlike AdaCuRL, INTELLECT-3 does not explicitly address catastrophic forgetting through bucket merging.

Adaptive Environments

An extension to adaptive curriculum learning is to make the environment itself adaptive. Instead of fixed rubrics/reward functions, we can update them based on the model’s performance.

DR Tulu (Shao et al., 2025) introduced evolving rubrics for open-ended tasks. Static RLVR only works for short-form QA with verifiable answers. RLER (Reinforcement Learning with Evolving Rubrics) creates dynamic rubrics that co-evolve with the policy model, incorporating newly searched information from the environment rather than just LM parametric knowledge. Static rubrics are vulnerable to reward hacking; evolving rubrics adapt to training dynamics.

Tool Calling: From LLMs to Agents

To convert benchmark scores into real-world value ($$$), we want LLMs to perform tasks beyond their parametric knowledge like searching the web, reading files, querying databases, calling APIs, writing reports, etc. A number of SFT datasets already exist to train good tool calling models:

| Dataset | Size | APIs | Source | Quality Issues |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ToolBench | 126K pairs | 16,464 | RapidAPI | 50% query hallucination rate |

| xLAM-60k | 60K | 3,673 | APIGen pipeline | 95%+ verified correct |

| Glaive v1/v2 | 52K / 113K | Synthetic | Proprietary generation | Model may hallucinate functions |

| API-Blend | ~160K | Multi-source | Curated transforms | Limited nested/parallel calls |

| Gorilla/APIBench | 11K | 1,645 | HF/TorchHub/TensorHub | No execution verification |

| ToolAlpaca | 3,938 | 400+ | Multi-agent simulation | Limited tool diversity |

Real World Tool Use is Hard

Even after achieving a good general purpose tool calling model, real world tool use is still hard for LLMs because:

- Coverage of your tools: Public datasets cover generic APIs like weather, booking, search. But if you're building an agent for your company's internal systems, there's no dataset for your proprietary CRM or custom database schema. You need to generate environments reflecting your specific tool interfaces.

- Multi-turn and error handling: Most datasets focus on single-turn function calling: user asks, model calls function, done. Real agents need to handle failures gracefully, ask clarifying questions, and chain tools across turns. This multi-turn data is harder to find and harder to synthesize.

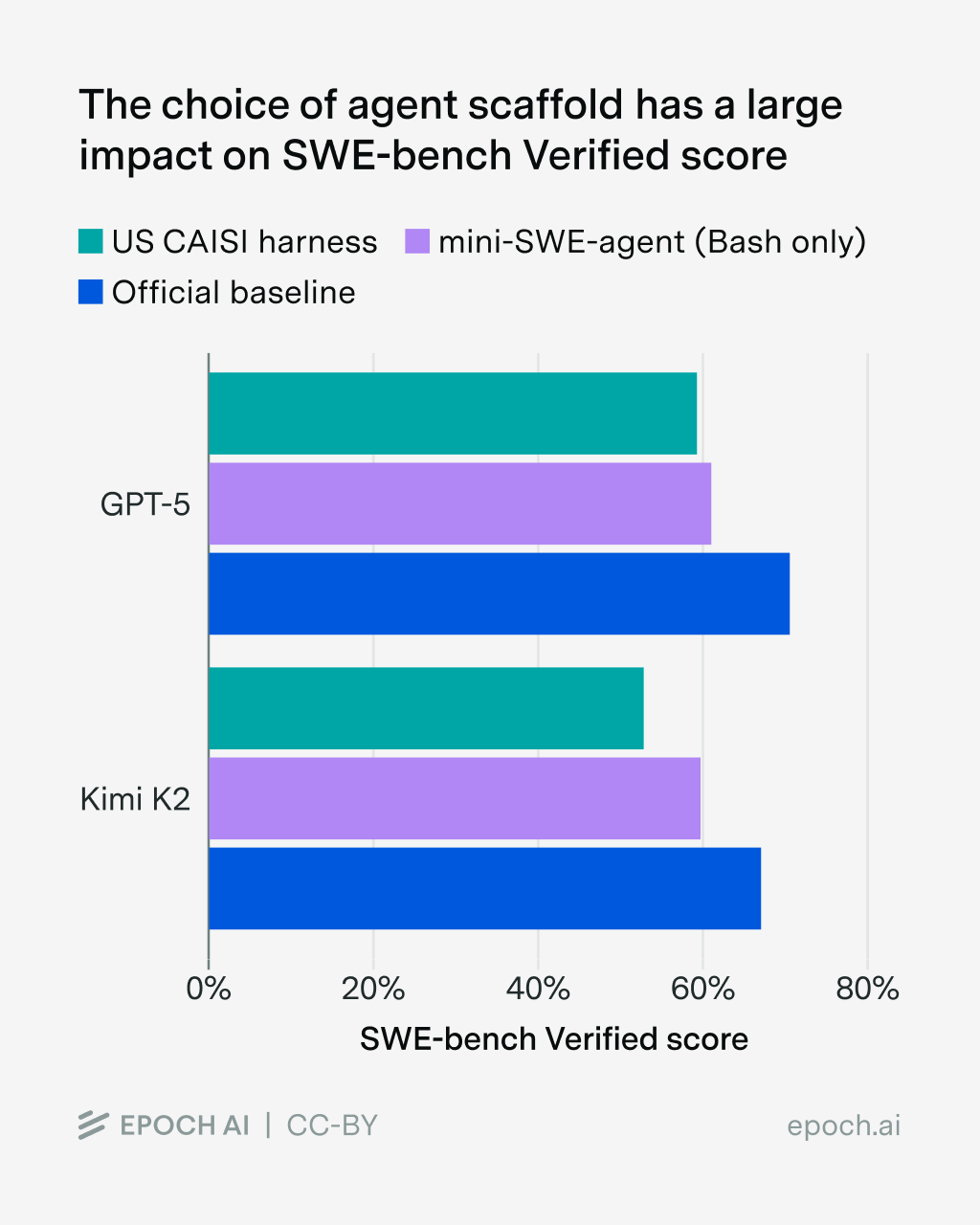

- Scaffolding matters: The scaffold, the orchestration layer around your agent (e.g., Claude Code, OpenHands), controls how tools are presented, ordered, and filtered to the agent's context. These details compound into big performance swings: on SWE-bench Verified, simply switching the scaffold causes up to 11% difference for GPT-5 and 15% for Kimi K2. In fact, the choice of scaffold has the single biggest impact on overall agent performance. This is why you need to train and evaluate on environments that mirror your actual deployment, not just generic benchmarks.

Figure: The choice of agent scaffold has a large impact on SWE-bench Verified score. Source: Epoch AI - Cost and infrastructure: Even once you've defined your custom environment, hitting live APIs for thousands of training queries is slow, costly, and sometimes impractical—APIs may require authentication, have rate limits, or charge per call.

To handle these challenges, we need synthetic environments reflecting our specific tools, workflows, and orchestration. But do we actually need to hit real APIs to train on them?

Simulating Tool Responses

In nearly all cases, the answer is no—and it’s usually undesirable to do so. Instead, researchers have used two strategies:

1. Mock implementations: For certain tools, you can write a simple function that mimics the API. For example, for a get_exchange_rate(base, target) tool, you might implement a stub that returns a made-up exchange rate. This was done in the BFCL evaluation when the authors manually wrote Python functions for things like weather info or mortgage calculations so that they could execute the model’s function calls and check correctness [Source: BFCL]. In training data, however, it’s more common to simply embed an example response directly rather than executing a stub on the fly.

2. LLM-based simulation: An intriguing byproduct of these efforts is that the LLM itself can serve as a mock API server. Instead of hitting real external services during training (which is slow, costly, and potentially insecure), one can prompt an LLM to pretend to be the tool. For instance, given a function spec like get_weather(city) and some internal knowledge or sample data, the LLM can generate a plausible response ({"temp": 15, "condition": "Cloudy"}) which is then fed back to the agent model. The big advantage is flexibility: you can generate infinite variations of tool responses (including erroneous ones) to make the model robust, and you don’t need your actual API keys during training. The downside is that a simulator might not capture every nuance of a real tool’s behavior, so a mix of simulated and real testing is ideal.

Is this simulation realistic? It can be. Recent research has started to quantitatively evaluate how well an LLM can imitate a real API. MirrorAPI (Guo et al., 2025) is a system that fine-tunes an LLM specifically to mimic API outputs given the API documentation and a user query. They measured the similarity between the simulated responses and the true API responses across hundreds of real API calls. They found that the fine-tuned simulator achieved very high BLEU scores and cosine similarity to the real outputs. In other words, a well-trained “API simulator” can produce outputs almost indistinguishable from the real API, including error messages and edge-case behaviors. This finding has big implications. MirrorAPI was used to create a complete simulated tool-use benchmark, StableToolBench, where the agent interacts with simulated APIs – avoiding all the unpredictability of calling external services during evaluation.

Context Confusion: The Tool Complexity Problem

The rise of MCP (Model Context Protocol) and agentic frameworks (PydanticAI) made it easier to connect many tools to an LLM. But this tool cocktail can lead to Context Confusion, which usually manifests as benchmark score degradation. Specifically, when there’s only one tool available, agent’s downstream performance is higher than when the model must choose among many.

A curriculum approach might work here: master single tools first, then tool families (all file operations, all web APIs), then full environments with all tools available. The MCP ecosystem is expanding with standardized interfaces, but the fundamental challenge remains—more tools means more interference during training. This is another reason why your scaffold matters (see point 3 above): how tools are ordered, filtered, and presented in context directly affects whether the agent gets confused by too many options.

Multi-Turn RL Training

With the right verification, reward shaping, and curriculum design, we can train an LLM that’s great at single-turn math and code. But real-world agents are messier—they need to ask clarifying questions, fix mistakes, recover from errors, and chain tools across multiple steps.

What Changes in Multi-Turn?

Single-turn RL is conceptually simple: one prompt → one response → one reward. Multi-turn introduces new challenges:

| Challenge | Single-Turn | Multi-Turn |

|---|---|---|

| Credit assignment | Direct: response → reward | Delayed: which turn caused failure? |

| State management | Stateless | Conversation history, tool state |

| Stopping criteria | Always done after 1 turn | When to stop? Max turns? Success signal? |

| Reward timing | End of response | End of episode? Per-turn? |

The fundamental question becomes: how do you assign reward to individual turns when success depends on the whole trajectory?

Trajectory-Level vs Turn-Level Rewards

Most multi-turn RL work uses trajectory-level rewards—you get a single reward at the end of the episode based on task success. This is simpler but suffers from credit assignment problems (which turn was good/bad?).

An alternative is turn-level rewards, where each turn gets partial credit. But this reintroduces reward hacking risks we discussed earlier—the agent might learn to maximize intermediate rewards without solving the task.

OpenHands (Wang et al., 2024) and SWE-agent (Yang et al., 2024) both use trajectory-level binary rewards (did you solve the GitHub issue?) with the simplicity of: reward = 1 if tests pass, else 0.

Environment Architecture

Libraries like verifiers handle multi-turn complexity through environment inheritance, where each layer adds new capabilities:

| Layer | What it adds |

|---|---|

| Environment | Base protocol: reset(), step(), reward |

| ↳ MultiTurnEnv | Conversation history, turn limits, stopping conditions |

| ↳ ToolEnv | Parses tool calls, executes them, returns results |

| ↳ StatefulToolEnv | Persistent state across tool calls (files, DBs) |

| ↳ SandboxEnv | Isolated execution environments |

| ↳ CodeEnv | Code execution with safety boundaries |

Each layer builds on the previous. The key insight: multi-turn environments need to manage state that persists across the episode—file changes, database writes, git commits. This is what makes sandboxing critical.

These abstractions hide real operational complexity—especially at scale. Consider what’s required to run agents on SWE-bench:

For each task instance, we need to:

- Clone the target repository (could be Django, scikit-learn, matplotlib—each with different dependencies)

- Checkout the specific base commit that existed before the bug was introduced

- Install the project’s dependencies in an isolated environment

- Apply any environment-specific patches or configurations

- Set up the test harness to verify the fix

The infrastructure cost adds up:

- Docker images for SWE-bench can reach 160GB+ total across all project environments

- Each environment requires 16GB+ RAM for comfortable operation

- The original SWE-bench Docker setup consumed 684 GiB before optimization efforts brought it down to ~67 GiB

- Building these images from scratch can take hours

This is why SWE-bench agents use pre-built Docker images per repository. We can’t afford to pip install Django’s entire dependency tree every time our agent wants to attempt a fix. The environments must be ready to go, with the exact commit checked out and dependencies pre-installed.

This complexity makes robust sandboxing essential: we need isolation that can be spun up reliably, thousands of times, without breaking the training run.

Sandboxing

Running model-generated code during RL training is an operational challenge that might break a multi-week training run. Without proper isolation, a single malicious or buggy code snippet can compromise the entire training run.

Why Sandboxing Matters

Running model-generated code on the training cluster is a terrible idea because:

- Segfaults and crashes: One segfault or infinite loop shouldn’t kill a 20-day training run.

- Resource exhaustion: Memory bombs, fork bombs and disk filling attacks are trivial to generate and can easily overwhelm the training cluster.

- Security breaches: The model might curl the internal APIs, read environment variables with API keys, or worse.

The risks compound at scale. When we’re running thousands of concurrent rollouts, the probability of hitting an edge case approaches certainty.

Scaling Sandboxed Execution

For efficient RL training, we need to run thousands of environment instances in parallel. For instance, Prime Intellect reports running 4,000 concurrent sandboxes during their RL training.

This creates a trade-off between isolation strength and startup latency:

- Containers (Docker, Podman): Fast startup (often ~10–100ms when warm), decent isolation, but they share the host kernel. A kernel exploit could escape the sandbox.

- MicroVMs (Firecracker): VM-grade isolation with near-container ergonomics; used by AWS Lambda, with boot times often cited on the order of ~100ms in optimized setups. E2B builds on Firecracker to offer sandboxed code execution as a service.

You may also see gVisor mentioned in this space. It’s not a microVM but a container sandbox that intercepts syscalls to reduce the host kernel attack surface.

- Full VMs: Strongest isolation, but slower startup and higher resource overhead—often too costly at ~4,000 concurrent instances.

Most production RL systems end up with hardened containers, and reach for microVMs when they need stronger guarantees. In practice, you usually want the lightest isolation that still keeps you safe—simple arithmetic doesn’t need a VM, but arbitrary shell commands often do.

Practical Recommendations

For prototyping and small-scale experiments:

- Use E2B or Modal — the managed overhead is worth it

- Focus on your environment logic, not infrastructure

For production RL training:

- If you need maximum control: build on Kubernetes + gVisor with custom orchestration

- If you need speed to production: E2B (self-hosted) or Modal with reserved capacity

- Budget ~20–30% of engineering time for sandbox infrastructure if you’re building custom

Beyond Python: The Multi-Language Reality

The sandboxing challenge compounds when we move beyond Python. Real-world tool use spans a much wider landscape, and each domain brings its own isolation requirements:

- Different programming languages: Python, JavaScript, Rust, Go, C++—each with its own runtime, package manager, and execution semantics. Training on Rust compilation errors or JavaScript async patterns requires those actual environments, not simulations.

- Database environments: SQL queries against real engines (Postgres, MySQL, SQLite). Learning query optimization requires actual query planners—mocks won’t teach your model about index selection.

- CLI environments: Shell commands, file system operations, piping, environment variables. These need particularly careful sandboxing given shell’s power to modify the system.

- SWE environments: Full development setups with git, package managers, build tools, linters, test runners. SWE-agent and OpenHands demonstrate the infrastructure complexity here.

- Computer use: GUI interactions, browser automation, screenshot-based feedback loops—requiring display servers and rendering infrastructure.

Each domain requires different isolation strategies, resource limits, and verification approaches. There’s no single solution that covers the full landscape, which is why building robust RL environments remains an active area of infrastructure investment.

Conclusion

We are shifting from curating static datasets to engineering dynamic environments. This turns data preparation into a systems problem: you need sandboxes that don’t leak, verifiers that don’t hallucinate, and curricula that adapt to the model’s progress.

The model will optimize whatever signal you give it. If the environment allows reward hacking, the model will hack it. If the sandbox is slow, training stalls. The difficulty lies in constructing a feedback loop that is both tight enough to provide signal and robust enough to scale. The algorithm matters less than the integrity of the environment it runs in.

References

- DeepSeek-R1: Incentivizing Reasoning Capability in LLMs via Reinforcement Learning - DeepSeek-AI, 2025

- INTELLECT-3: Distributed Reinforcement Learning with Synthetic Data for AGI - Prime Intellect Team, 2025

- AdaRFT: Efficient Reinforcement Finetuning via Adaptive Curriculum Learning - Shi et al., 2025

- AdaCuRL: Adaptive Curriculum Reinforcement Learning - Li et al., 2025

- DOTS: Learning to Reason Dynamically in LLMs via Optimal Reasoning Trajectories Search - Yifan et al., 2025

- Light-R1: Curriculum SFT, DPO and RL for Long COT - Wen et al., 2025

- DeepScaleR: Surpassing O1-Preview with a 1.5B Model by Scaling RL - Luo et al., 2025

- SimpleRL-Zoo: Investigating and Taming Zero Reinforcement Learning for Open Base Models - Song et al., 2025

- RLVE: Scaling Up Reinforcement Learning for Language Models with Adaptive Verifiable Environments - Zeng et al., 2025

- DR Tulu: Reinforcement Learning with Evolving Rubrics for Deep Research - Shao et al., 2025

- CURE: Code Understanding and Repair through Co-Evolving Models - Yin jie et al., 2025

- EvalPlus: Rigorous Evaluation of LLM-Synthesized Code - Liu et al., 2023

- CodeRL: Mastering Code Generation through Pretrained Models and Deep RL - Le et al., 2022

- ToolLLM: Facilitating Large Language Models to Master 16000+ Real-world APIs - Qin et al., 2023

- APIGen: Automated Pipeline for Generating Verifiable Function Calling Datasets - Liu et al., 2024

- SpecTool: A Benchmark for Characterizing Errors in Tool-Use LLMs - Kokane et al., 2024

- Berkeley Function Calling Leaderboard (BFCL) - Gorilla Team, 2024

- MirrorAPI: Imitating APIs via Fine-Tuned LLMs - Guo et al., 2025

- StableToolBench: A Stable Large-Scale Benchmark for Tool Learning - Guo et al., 2025

- OpenHands: An Open Platform for AI Software Developers as Generalist Agents - Wang et al., 2024

- SWE-agent: Agent-Computer Interfaces Enable Automated Software Engineering - Yang et al., 2024

- Faulty Reward Functions in the Wild - OpenAI, 2016

- Recent Reward Hacking Research - METR, 2025

- OpenAI o3 Evaluation Report - METR, 2025

- RE-Bench: Evaluating Frontier AI R&D Capabilities - METR, 2025

- Sakana AI Walks Back Claims About AI Speeding Up Model Training - TechCrunch, 2025

- Self-Training Large Language Models for Tool Use - Luo et al., 2024

- How Kimi K2 Became One of the Best Tool-Using Models - Breunig, 2025

- Why Benchmarking is Hard: Scaffold Effects on SWE-bench - Epoch AI, 2025

- SWE-bench Docker Optimization - Epoch AI, 2025

- How Contexts Fail and How to Fix Them - Breunig, 2025

- verifiers: A Library for Multi-Turn RL Training - Prime Intellect, 2025

Feel free to reach out on Twitter, Linkedin, GitHub, or Mail.

Leave a comment