CUDA Studylog 3 - Tiling and Shared Memory for Matrix Multiplication Optimization

Introduction

In our previous post, we implemented a naive CUDA matrix multiplication kernel and identified that it’s not efficient. In this post, we’ll explore various optimization techniques to address these issues and significantly improve performance.

Take a look at the naive implementation again:

__global__ void matmul_naive(float* A, float* B, float* C, int M, int N, int K) {

int row = blockIdx.y * blockDim.y + threadIdx.y;

int col = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

if (row < M && col < N) {

float sum = 0.0f;

for (int k = 0; k < K; k++) {

sum += A[row * K + k] * B[k * N + col];

}

C[row * N + col] = sum;

}

}

Problems with Naive Implementation

Problem 1: Global Memory Access

The main issue with this implementation is the following code snippet:

for (int k = 0; k < K; k++) {

sum += A[row * K + k] * B[k * N + col];

}

Note: As the matrices, A [M x K] and B [K x N] are large, they are stored in global memory (GRAM).

In each iteration of the for-loop, we are reading twice from the global memory - one element from A and one element from B. This means for each element in the output matrix, we’re performing K * 2 global memory reads.

This is a significant problem because global memory access is extremely slow compared to other types of memory access in CUDA. Each global memory access can take hundreds of clock cycles, making this a major performance bottleneck.

Problem 2: Lack of Coalesced Memory Access

The second major issue relates to how we’re accessing memory. Let’s break down what’s happening:

- For computing C[0,0], a thread needs:

- Entire row A[0,:]

- Entire column B[:,0]

- For computing C[0,1], another thread needs:

- The same row A[0,:] again

- Column B[:,1]

- This pattern continues, meaning:

- Multiple threads are redundantly reading the same rows from A

- Threads are reading B in a column-wise manner

This memory access pattern is problematic for two reasons:

-

Redundant Reads: The same data from matrix A is being read multiple times by different threads, wasting precious memory bandwidth.

-

Non-Coalesced Access: When reading from matrix B, we’re accessing memory in a column-wise fashion. In CUDA, memory is organized in a way that row-wise (coalesced) access is much more efficient. Column-wise access means:

- Each thread is reading from different memory segments

- We can’t take advantage of CUDA’s memory coalescing

- Memory transactions can’t be combined, leading to more separate memory operations

Here’s a visual representation of the problem:

As shown in the diagram above, we have two problematic memory access patterns:

- For Matrix A:

- Thread 0 reads all elements in Row 0 ($a_{00}, a_{01}, a_{02}, a_{03}$)

- Thread 1, calculating the next element in the output, needs to read the exact same Row 0

- This redundant reading of the same row wastes memory bandwidth

- For Matrix B:

- Thread 0 needs to read all elements in Column 0 ($b_{00}, b_{10}, b_{20}, b_{30}$)

- Thread 1 needs to read all elements in Column 1 ($b_{01}, b_{11}, b_{21}, b_{31}$)

- This column-wise access pattern is non-coalesced, meaning each thread’s memory access can’t be combined into a single transaction

The blue arrow in Matrix A shows the coalesced (efficient) memory access pattern, while the red arrow in Matrix B shows the non-coalesced (inefficient) pattern. When threads access memory in a non-coalesced way, they can’t take advantage of CUDA’s memory coalescing features, resulting in multiple separate memory transactions instead of a single combined one.

Optimization Solution

Using Shared Memory

The key idea is to use CUDA’s shared memory - think of it as a super-fast, small cache that all threads in a block can access together. It’s like having a small whiteboard that a group of students can all read from and write to quickly! This leads us to the question, why can’t we move A and B matrices into shared memory from Global Memory? However, unlike Global memory, Shared-memory is small and can only accomodate limited amount of data.

Therefore, we need to find a way to load only a portion of A and B matrices into shared memory. Here, we’ll use a technique called tiling.

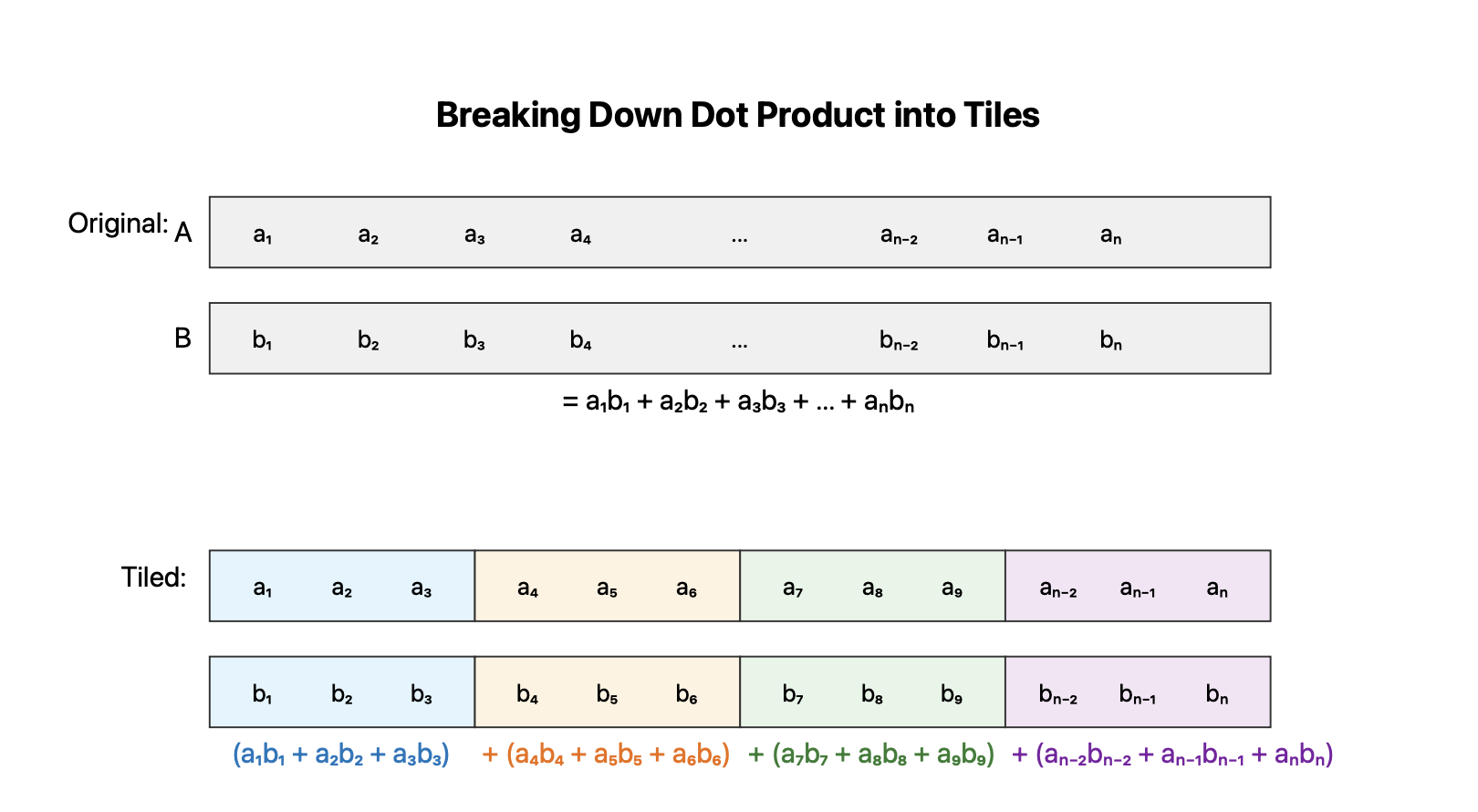

Understanding Tiling

We can break our matrix multiplication down into smaller, more manageable chunks. This is where tiling comes in - it’s like solving a big puzzle by working on smaller pieces first.

Consider how we compute C[i,j]. We need to perform a dot product between:

- Row i of matrix A (size K)

- Column j of matrix B (size K)

Instead of doing this all at once, we can break this computation into smaller computational chunks ( or “tiles”).

Looking at the diagram above, we can see that a dot product can be naturally broken down into smaller chunks or “tiles”. Each tile computes a partial dot product, and these partial results are then summed to get the final result.

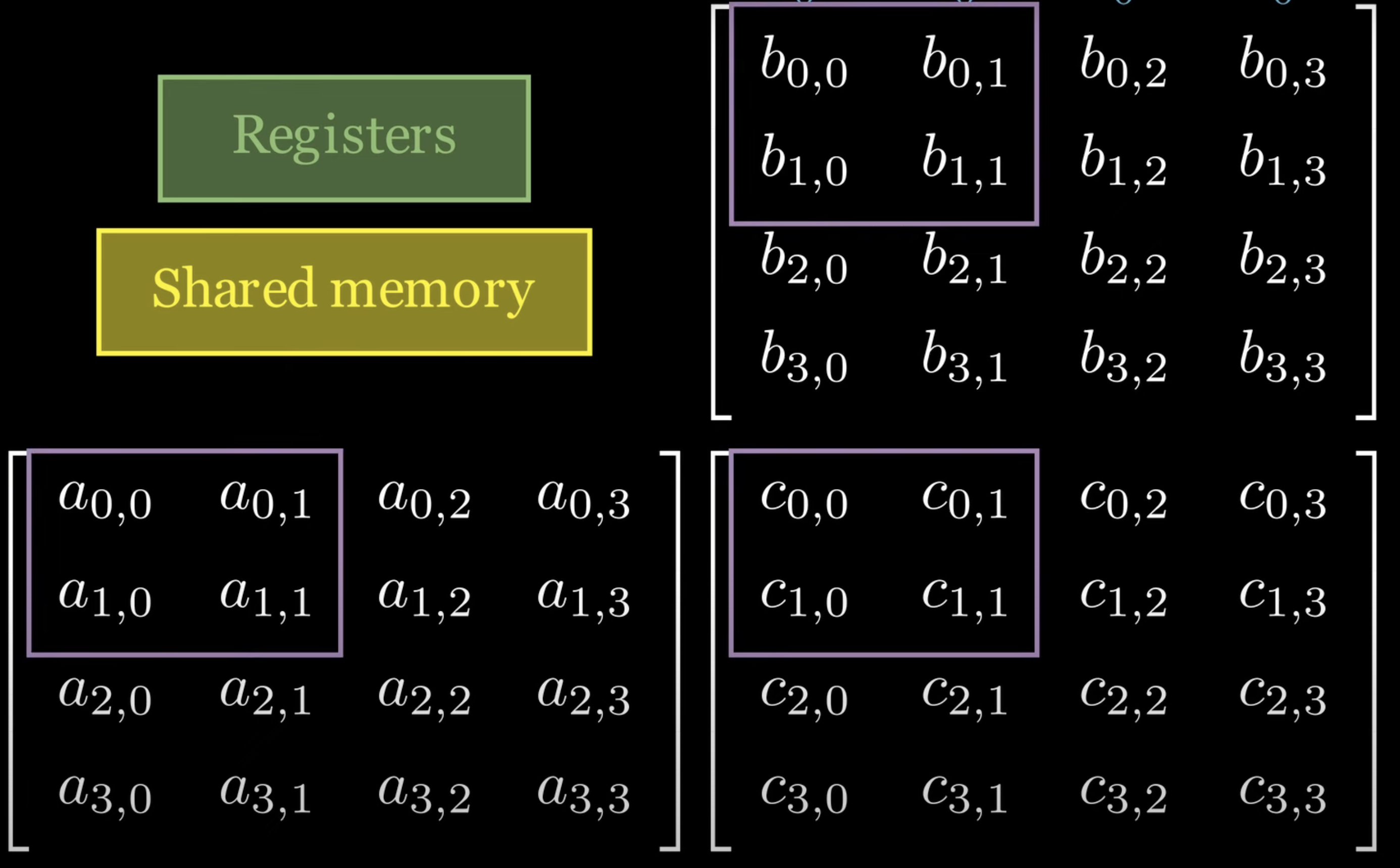

Implementing Tiling with Shared Memory

Looking at the image, we can see three different memory hierarchies represented: registers (in green), shared memory (in yellow), and the matrices A, B, and C. The purple boxes within each matrix represent our tiles - the subsets of the matrices that we’ll work with at any given time.

Let’s break down how tiling works with shared memory:

- Each tile (purple box) represents a portion of the matrix that we’ll load into shared memory. In our example, we’re using 2x2 tiles, though in practice, tile sizes are usually larger (e.g., 16x16 or 32x32) for better performance.

- For matrices A and B, we load their respective tiles into shared memory:

- For matrix A, we load a 2x2 section ($a_{00}, a_{01}, a_{10}, a_{11}$)

- For matrix B, we load the corresponding 2x2 section ($b_{00}, b_{01}, b_{10}, b_{11}$)

- Once these tiles are in shared memory, all threads in the block can access them quickly to compute their portion of matrix C.

- Note that in the output matrix C’s tile, we can compute each element of the tile by performing a dot product of the elements of the corresponding tiles of A and B.

Looking at the animated visualization, we can see how tiling breaks down the matrix multiplication process:

1. Load Phase

- Each block loads a 2x2 tile from matrices A and B into shared memory (shown in purple boxes)

- This means instead of accessing global memory repeatedly, we only need to perform one bulk load operation

2. Compute Phase

- Once the tiles are in shared memory, threads can quickly access these values

- Each thread computes its portion of the partial dot product using the values in shared memory

- These intermediate results are stored in registers (shown in the green box)

3. Accumulate and Slide

- After computing the partial results, the tiles “slide” to the next position

- For matrix A, we move horizontally to the next tile

- For matrix B, we move vertically to the next tile

- This process continues until we’ve covered all tiles needed for our final result

Here’s how we would implement this optimization in CUDA:

template<int TILE_SIZE>

__global__ void matmul_tiled(float* A, float* B, float* C, int M, int N, int K) {

__shared__ float tile_A[TILE_SIZE][TILE_SIZE];

__shared__ float tile_B[TILE_SIZE][TILE_SIZE];

// Calculate global indices

const int row = blockIdx.y * blockDim.y + threadIdx.y;

const int col = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

// Local thread indices

const int tile_local_row = threadIdx.y;

const int tile_local_col = threadIdx.x;

float sum = 0.0f;

// Calculate number of tiles needed

const int num_tiles = (K + TILE_SIZE - 1) / TILE_SIZE;

// Iterate over tiles

for (int tile_idx = 0; tile_idx < num_tiles; tile_idx++) {

// Calculate starting position for this tile

const int tile_offset = tile_idx * TILE_SIZE;

// Load elements into tile_A

const int a_col_idx = tile_offset + tile_local_col;

if (row < M && a_col_idx < K) {

tile_A[tile_local_row][tile_local_col] = A[row * K + a_col_idx];

} else {

tile_A[tile_local_row][tile_local_col] = 0.0f;

}

// Load elements into tile_B

const int b_row_idx = tile_offset + tile_local_row;

if (b_row_idx < K && col < N) {

tile_B[tile_local_row][tile_local_col] = B[b_row_idx * N + col];

} else {

tile_B[tile_local_row][tile_local_col] = 0.0f;

}

__syncthreads();

// Compute partial dot product for this tile

for (int k = 0; k < TILE_SIZE; k++) {

sum += tile_A[tile_local_row][k] * tile_B[k][tile_local_col];

}

__syncthreads();

}

// Write final result

if (row < M && col < N) {

const int c_idx = row * N + col;

C[c_idx] = sum;

}

}

Let’s break down the key optimizations in this implementation:

1. Shared Memory Usage

__shared__ float tile_A[TILE_SIZE][TILE_SIZE];

__shared__ float tile_B[TILE_SIZE][TILE_SIZE];

We declare shared memory arrays to store our tiles The TILE_SIZE is typically set to 16 or 32 for optimal performance

2. Tile Loading

tile_A[tile_local_row][tile_local_col] = A[row * K + a_col_idx];

tile_B[tile_local_row][tile_local_col] = B[b_row_idx * N + col];

- Each thread loads one element from global memory into shared memory

- Boundary checks ensure we don’t access out-of-bounds memory

- The loading is done collaboratively by all threads in the block

3. Synchronized Loading

__syncthreads();

We use __syncthreads() to ensure all threads have finished loading data into shared memory before computation begins

This synchronization is crucial to prevent race conditions

4. Computation

for (int k = 0; k < TILE_SIZE; k++) {

sum += tile_A[tile_local_row][k] * tile_B[k][tile_local_col];

}

The actual computation now uses shared memory instead of global memory, making it much faster.

Performance Impact

The tiled implementation typically offers significant performance improvements:

1. Reduced Global Memory Access

Instead of K*2 global memory accesses per output element, we now only need (K/TILE_SIZE)*2 global memory loads per thread, followed by K faster shared memory accesses. Shared memory access is much faster than global memory access (usually 20-30x faster). This results in a significant performance improvement.

2. Better Memory Coalescing

Memory accesses are now organized in a way that better utilizes CUDA’s memory coalescing capabilities This means fewer memory transactions and better bandwidth utilization

3. Data Reuse

Each loaded tile is used by multiple threads within the block This significantly reduces redundant memory access

Conclusion

In this post, we’ve explored two major issues with our naive implementation and how tiling can help us overcome them.

Leave a comment